China economy update - May 2024

The Chinese economy stands at an inflexion point. This is a summary of how the Chinese economy got here.

The last phase in its investment-driven growth model revolved around the property market and has culminated in over-leveraged real estate firms many of whom ran the risk of defaulting. In realisation of the problem, Beijing too has sought to deflate the property bubble since 2020. The spectacular debt-fuelled growth of the property market has finally stalled.

In its search for alternative drivers of growth and also motivated by geopolitical considerations, in the latest turn in the investment-driven model, the central government has turned its attention to renewable power equipment, EVs, semiconductor chips, and other technology sectors. The result has been relentless capacity addition. Compounding matters, the cooling economy and stumbling property market have reduced the demand for steel, construction equipment, and in several other industries. Domestic capacity utilisation has slumped to the lowest since early 2020. The excess capacity is now translating into a surge in exports. Nowhere has this been more significant than in cars and EVs, where China has eclipsed Japan to emerge as the world’s biggest car exporter.

The latest surge in cheap exports has generated strong opposition across trading partners in developed and developing countries. The US has imposed bans on imports of Chinese EVs and others have raised tariffs or are in the process of doing so. The EU has launched a Foreign Subsidies Regulation primarily to protect its domestic industry from cheap Chinese imports and investments that imperil national security. Protectionism against cheap Chinese exports has become the global norm. It has become clear that the latest phase in the investment-driven export-led growth of the Chinese economy has run its course. Ironically, for all its focus on self-reliance, China has become more reliant on the world economy to absorb its surplus capacity exports and sustain its economic growth.

In the circumstances, the only option left for China is to rebalance its economy away from investments to consumption. It’ll also shift demand away towards domestic consumers and markets. However, the Xi Jinping government has been consistent in its reluctance to adopt this strategy. It appears to believe that it can continue its strategy of investing and exporting its way out.

Now some links on the above.

The property market has been in a slump for the last three years. Realising the distorted role of real estate, the government started tightening the market in August 2020 with its three red lines initiative to restrict debt to the sector. It has tried several follow-up measures since. But it has stayed away from bailing out the private property developers, several of whom, including some of the biggest, have defaulted and failed. I have blogged earlier that real estate had come to occupy a disproportionate share of economic output and its valuations were central to local government revenues.

The central government’s efforts to rein in the property market slump have failed so far. The number of unsold apartments is rising rapidly.

After the defaults and even failures of several top private property developers, the real estate slump is now threatening state-owned developers. The Bloomberg article writes

Because of the predominant presales model, money from contracted sales — not bank loans — is the biggest source of financing for all builders. The longer Xi waits, the bigger his rescue package will have to be.

Beijing hopes that the measures it has taken will allow a gradual shake-up and normalisation of the property market - the heavily indebted private developers will exit leaving only a handful of bigger ones. But as a Peterson Institute Paper writes, it’s unlikely that the property market will have a soft landing.

The excess capacity problem manifests across the economy. The overcapacity problem in real estate has cascaded across several other related sectors.

The industries suffering most from overcapacity today are casualties of China’s ill-starred property sector, where private and state developers have long vied with each other. A collapse in property sales has left many neighbouring industries looking oversized. Adam Wolfe of Absolute Strategy Research cites the example of excavators. Until mid-2021, China bought most of the diggers it produced. But domestic sales have plunged, meaning China has abruptly emerged as the world’s biggest exporter of such equipment. Another case is cement, and similar materials, where capacity utilisation is down to 62%.

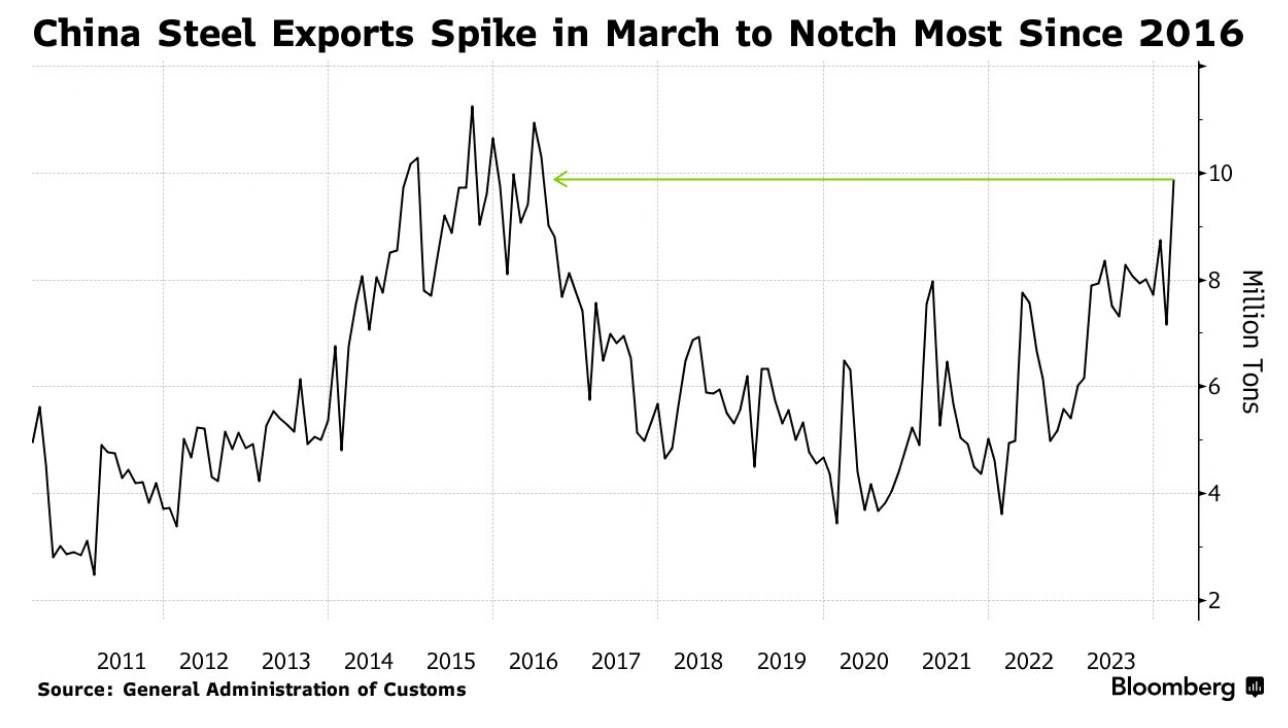

Steel output has remained consistently in the 1 billion tonne range for the last several years, despite falling domestic demand.

Steel exports recently hit the highest since 2016.

The latest sector to have built up excess capacity is automobiles. And the excess capacity is now showing up as surging exports.

The NYT has this about the capacity glut in the automobile sector.

China has more than 100 factories with the capacity to build close to 40 million internal combustion engine cars a year. That is roughly twice as many as people in China want to buy, and sales of these cars are dropping fast as electric vehicles become more popular… Dozens of gasoline-powered vehicle factories are barely running or have already been mothballed... Sales of gasoline-powered cars plummeted to 17.7 million last year from 28.3 million in 2017... That drop is equivalent to the entire European Union car market last year, or all of the United States’ annual car and light truck production... with new electric car factories opening and few older factories closing, capacity utilization across the entire industry fell to 65 percent in the first three months of this year from 75 percent last year and 80 percent or more before the Covid-19 pandemic, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. Without a big burst of exports last year, the industry would have operated even further below full capacity.

The capacity glut has resulted in a surge in automobile exports.

Just four years ago, China was a weakling in car exports, shipping one million low-priced cars a year mainly to less affluent markets in the Mideast and elsewhere. China has since surpassed Japan and Germany by a wide margin to become the world’s largest car exporter. Shipments are running at an annual pace of nearly six million cars, sport utility vehicles, pickups and vans. Three-quarters of these exports, particularly to Russia and to developing countries, are cars with gasoline engines, which fewer buyers in China want… China’s top leaders have heavily subsidized the research and production of battery electric cars for the past 15 years. Companies are ramping up their manufacturing of battery electric cars and building a fleet of ships to export them to distant markets, particularly in Europe. Automakers are introducing 71 models of electric cars in China this year, many of them loaded with advanced features and selling for less than comparably equipped cars in the West.

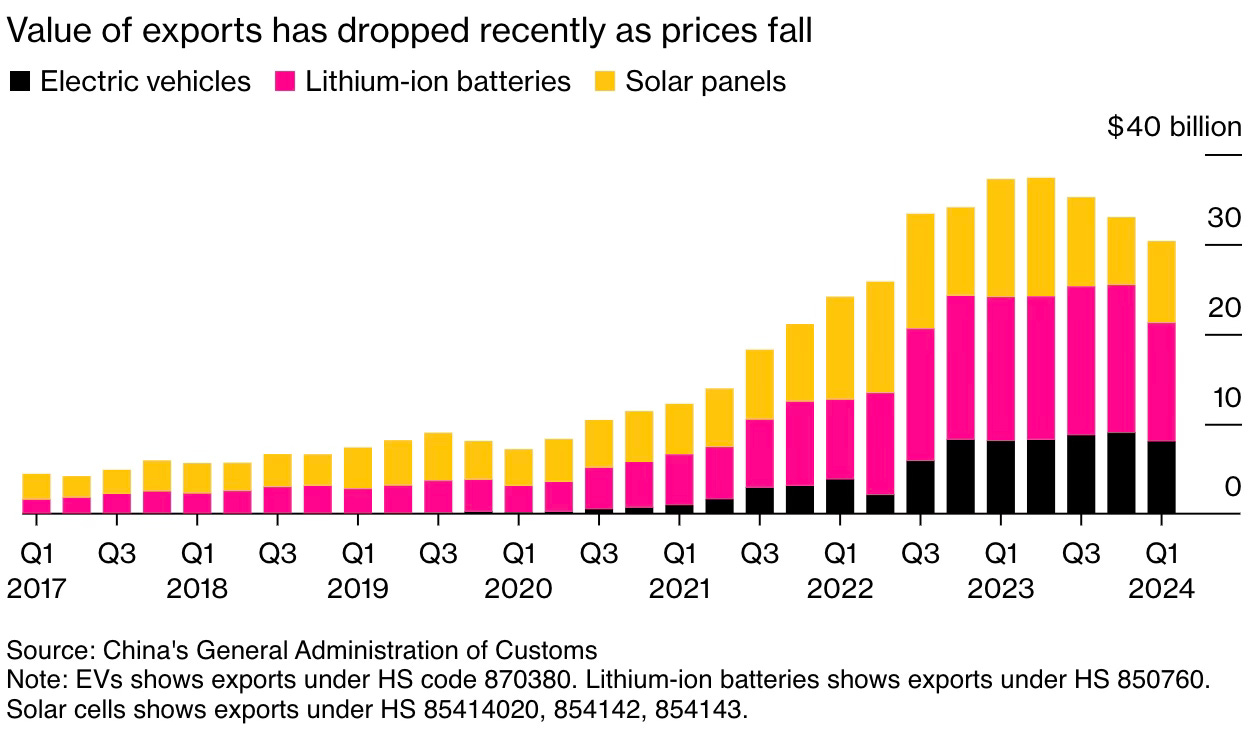

Bloomberg has an article on China's excess capacity problem. In the last three years, there has been a surge in exports of electric vehicles, Li-ion batteries, and solar panels. However, as prices have fallen and protectionist measures have risen, these exports have dropped.

The excess capacity has resulted in price drops and a deflationary environment.

Producer-price inflation has been negative for 18 months in a row. The gdp deflator, a broad measure of prices, has declined year on year for four consecutive quarters. When prices fall in an industry, it can be a sign that supply is excessive. When prices fall across an economy, it usually means demand is deficient, because confidence is low and macroeconomic policy too tight.

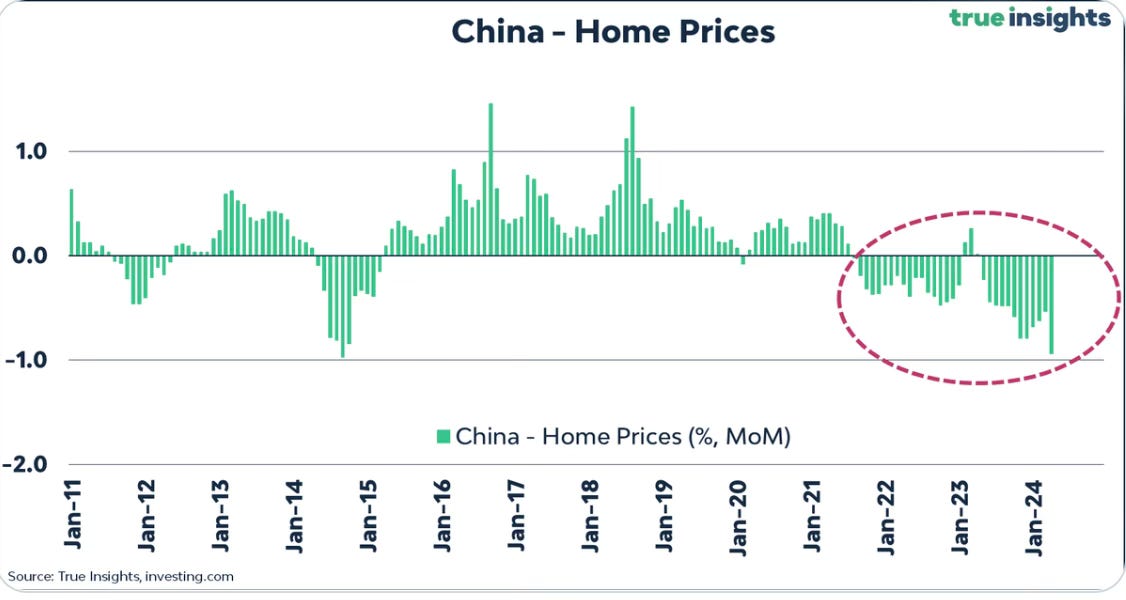

The worst manifestation of falling prices is the real estate market where home prices have been declining for 30 of the last 33 months!

Chinese home prices dropped a staggering 0.94% in April, the second-biggest decline on record. Home prices have declined in 30(!) out of the last 33 months. China's housing market recession has been going on for nearly three years. Retail sales, also published today, grew by a paltry 2.3%, way below the 3.7% growth expected. China is now floating the idea of buying massive amounts of unsold houses through local governments. However, the issue is that these are drowning in debt through their Local Government Financing Vehicles. The result will be the same as always and not characteristic of just China; more debt will have to be issued and then managed through low yields. China's 10-year bond yield is 2.32%, which is exceptionally low for a country that is supposedly growing at a 5% rate.

The profits of the solar industry have slumped following glut and price wars.

The investment-consumption imbalance in the Chinese economy becomes stark when compared to the other larger economies.

China’s investment to gross domestic product ratio, at more than 40 per cent last year, is one of the highest in the world, according to the IMF, while private consumption to GDP was about 39 per cent in 2023 compared to about 68 per cent in the US. With the property slowdown, more of this investment is pouring into manufacturing rather than household consumption, stimulating oversupply, western critics say. “China is responsible for one-third of global production but one-tenth of global demand, so there’s a clear mismatch,” US secretary of state Antony Blinken said in Beijing last week... China’s high national savings rates, which, at more than 47 per cent of GDP in 2022, are double the world average.

The excessive reliance on investment has hardly changed over the last two decades.

Further, there’s now evidence that the imbalance is worsening.

The April data just released clearly suggests a widening imbalance in the Chinese economy. While consumption notably surprised to the downside and deviated further from its pre-pandemic trend, industrial production has picked up and risen further above the pre-pandemic trend.

See this for a magnified view of the trend from 2019.

Michael Pettis has a nice summary of the economic imbalance problem.

China’s structurally-high domestic saving rate is the result of a decades-long development strategy in which income is effectively transferred from households to subsidise the supply side of the economy — the production of goods and services. As a result of these transfers, growth in household income has long lagged behind productivity growth, leaving Chinese households unable to consume much of what they produce. Some of these subsidies are explicit but most are in the form of implicit and hidden transfers. These include directed credit, an undervalued currency, labour restrictions, weak social safety nets, and overinvestment in transportation infrastructure. These various policies automatically force up Chinese savings. By effectively exporting excess savings through the subsidy of the production of goods and services, China is able to externalise the resulting demand deficiency...

China’s structurally-high domestic saving rate is the result of a decades-long development strategy in which income is effectively transferred from households to subsidise the supply side of the economy — the production of goods and services. As a result of these transfers, growth in household income has long lagged behind productivity growth, leaving Chinese households unable to consume much of what they produce. Some of these subsidies are explicit but most are in the form of implicit and hidden transfers. These include directed credit, an undervalued currency, labour restrictions, weak social safety nets, and overinvestment in transportation infrastructure. These various policies automatically force up Chinese savings. By effectively exporting excess savings through the subsidy of the production of goods and services, China is able to externalise the resulting demand deficiency.

The economic imbalance is also creating foreign policy tensions, and increasingly with other developing countries over cheap Chinese imports flooding their markets and destroying local industries.

Brazil’s industry ministry has launched a number of investigations into the alleged dumping of industrial products by China as Latin America’s largest economy reels from a wave of cheap imported goods. At the request of industry bodies, the ministry has in the past six months opened at least half a dozen probes on products ranging from metal sheets and pre-painted steel to chemicals and tyres... In addition to Brazil, China’s steel exports to Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia have risen sharply in recent months... In Thailand, the government has accused Chinese companies of evading anti-dumping duties, while industry groups have warned of big losses from cheaper steel in the market. Vietnam’s government has launched investigations into dumping of wind towers and some steel products from China after complaints from the local industries. In August last year Mexico imposed tariffs of 5-25 per cent on imports of hundreds of goods from countries with which it does not have a free trade agreement, with China being one of the countries most affected.

The US has continued to tighten the sanctions initiated under President Trump. Early last week, the US imposed 100% tariffs on electric vehicles, solar cells, semiconductors and advanced batteries, in addition to maintaining tariffs on more than $300 bn worth of Chinese imports put in place by the earlier administration. Such measures will invariably increase in the days ahead if China continues to pursue its current set of policies.

It’s becoming very clear that there are hard limits to the Chinese strategy of externalising its economic problems through aggressive exports. And we are already at those limits.

Amidst all this, the Chinese government announced the sale of 1 trillion yuan ($138 billion) special sovereign bonds (600 bn yuan for 30 years, 300 bn for 20 years, and 100 bn for 50 years) over the next six months, the fourth such sale in the past 26 years. These bonds are special in so far as they are not part of the fiscal deficit and can be used for any purpose. This was accompanied by a scheme to lend $41.5 bn to local governments and state-owned enterprises to buy up some of the vast unsold housing stocks. Beijing is clearly unwilling to give up on its investment-driven growth strategy.