Chinese economy update - October 2023

The Chinese economic story in recent years goes something like this. The country's economic growth, especially after the global financial crisis has been powered by high domestic savings, resources raised from property sales, and massive investments. The much-needed recalibration towards private consumption never happened, even as real-estate and public investments increased their already out-sized importance in economic growth. And with President Xi came a series of macroeconomic policy reversals, crackdowns on corruption, centralisation of powers, and deterioration of foreign relations.

The drivers of economic growth were already struggling before the pandemic, and the draconian pandemic policies and ratcheting Cold War with the US have exposed the latent weaknesses and excesses and threatens to take the economy to the brink. The disarray in the sector that constitutes the largest source of household savings has spooked consumer confidence and further dragged down growth in private consumption. It also threatens to have a knock-on impact across the economy.

The government has realised the need to wean the economy away from its excessive reliance on real estate and has refrained from intervening to prop up the declining property market. However, the escalating Cold War has made investments in technology sectors a priority for Xi. With real estate tanking and local governments heavily indebted, finding resources to support these investments is a problem. Trade, an important driver of the country's economic growth over the last quarter century is facing the headwinds of protectionism and a Cold War.

The traditional engines of growth have therefore stalled and the standard toolkit of public investment-based stimulus when faced with a crisis appears to have become blunt. Amidst all this, the government appears reluctant or unable to introduce policies that can boost private consumption. For a government that's happy to deploy policy levers, those like increased unemployment benefits and pensions, or direct transfers to households to boost spending, or tax cuts have been missing.

This blog post covers a series of the latest articles validating the story above.

Real estate is at the core of the problems and forms more than a quarter of economic output and atlas three-fifths of household savings. In 2015-16, in response to a teetering real estate market, the central bank unleashed an extraordinary blitz of lending that saw minimum down payments for buying housing being reduced triggering a housing construction boom, and vast sums were lent to local governments who splurged on infrastructure. This stimulus also triggered a wealth effect that sparked a spurt in consumption. Those debts are now coming home to roost.

Apartments were bought as investments to rent out, including by many Chinese families that saw an opportunity to accumulate wealth. But as more and more apartments were built, their value as rentals declined. Investors were left with apartments whose rent wouldn’t pay for their mortgages. In many cities, annual rent has been 1.5 percent or less of an apartment’s purchase price, while mortgage interest costs have been 5 or 6 percent.

Apartments in China are commonly delivered by builders without amenities like sinks and washing machines, or even basics like closets or flooring. Because rents are so low, many investors have not bothered to finish apartments over the past decade, holding newly built but hollow shells in the expectation of flipping them for ever-higher prices. By some estimates, Chinese cities now have 65 million to 80 million empty apartments. Demand for new apartments has now plummeted... The annual number of births and marriages has almost halved since 2016, eroding much of the need for people to buy new apartments. Prices for existing homes have fallen 14 percent in the past 24 months. Prices of new homes have not fallen as much, but only because local governments have told developers not to cut prices drastically. Sales of new homes have plunged as a result.

And the property market slowdown is not a sudden development, but has been salient in recent years. The number of home sales has been on a declining trend for each of the last four years.

This clearly points to a saturated and mature market, where the build-it-and-they'll-come approach will not work. The Chinese economy will have to get used to a secular decline in property demand and adjust to a much lower baseline reliance on the real estate market to power growth and as a revenue mobilisation source for public expenditures.

This is a good summary of the reasons for the economic weakness

China’s dependence on real estate was lucrative during what seemed like a never-ending building boom, but it has become a liability after years of excessive borrowing and overbuilding. When China was growing faster, the excesses were papered over as developers borrowed more to pay off mounting debts. But now China is struggling to regain its footing after emerging from the paralyzing pandemic lockdowns its leaders imposed, and many of its economic problems are pointing back to real estate.

Chinese consumers are spending less, in part because a slump in housing prices has affected their savings, much of which are tied up in property. Jobs tied to housing that were once abundant — construction, landscaping, painting — are disappearing. And the uncertainty of how far the crisis might spread is leaving companies and small businesses afraid to spend. Local governments, which rely on land sales to developers to pay for municipal programs, are cutting back on services. Financial institutions known as trust companies, which invest billions of dollars on behalf of companies and rich individuals, are staring at losses from risky loans handed out to real estate firms, prompting protest from angry investors.

The crisis is a problem of the government’s own making. Regulators allowed developers to gorge themselves on debt to finance a growth-at-all-costs strategy for decades. Then they intervened suddenly and drastically in 2020 to prevent a housing bubble. They stopped the flow of cheap money to China’s biggest real estate companies, leaving many short on cash. One after another, the companies began to crumble as they could not pay their bills. More than 50 Chinese developers have defaulted or failed to make debt payments in the last three years, according to the credit ratings agency Standard & Poor’s. The defaults have exposed a reality of China’s real estate boom: the borrow-to-build model works only as long as prices keep going up... In July, new-home sales at China’s 100 biggest developers fell 33 percent from a year earlier, according to data from the China Real Estate Information Corp. Sales also fell 28 percent in June.

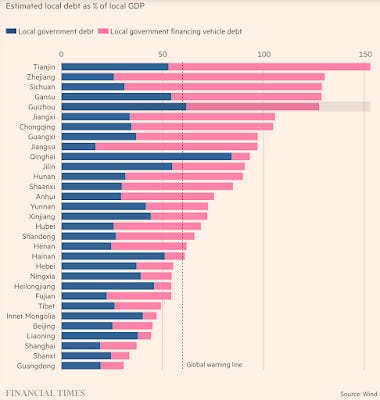

Local governments have been worst hit by the real estate crisis. They have long used Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) to raise debt and build infrastructure on behalf of local governments and land sales to generate the revenues to repay the loans. Banks have seen LGFVs as implicitly government-guaranteed. One estimate has put it at 94 trillion renminbi by the end of 2022. Two-thirds of local governments carry debts above the sustainability threshold.

Another fault line is the banks, which are heavily exposed to real estate. Nearly 40% of all bank loans are related to property. The enormous debt levels, oversupply of apartments, and consumers increasingly wary of buying are a clear danger for the banks and could put pressure on the government to bail them out.

Officials in Beijing have already taken some steps, underlining the difficult choices the real estate debt poses for policymakers. They have, for example, allowed banks to give extra time to borrowers before their loans come due, a step that risks doing little but kick the problem down the road. Yet that may send the message that both borrowers and lenders can continue pursuing incautious practices in the expectation of a bailout. And it delays the day when banks can lend to more productive ventures... China’s banking system, holding four-fifths of the country’s financial assets including most of the bonds, is far too big for the government to let fail...

The government directly or indirectly holds controlling stakes in practically all banks, giving it a powerful say over their fate even beyond having extensive regulatory powers. China’s financial system relies mostly on bank loans of a year or more, unlike the tradable securities that quickly tumbled in value in 2008, setting off the global financial meltdown. And regulators block most large movements of money in and out of the country, making China’s financial system nearly invulnerable to the kind of sudden departure of foreign money that touched off the Asian financial crisis in nearby countries in 1997 and 1998...

Nearly half of real estate-related lending in China consists of mortgages, mainly residential. Losses on mortgages are practically nonexistent as homeowners pay them on time or even early. China has long required far higher down payments than Western regulators — at least 20 or 30 percent of the purchase price for first-time home buyers, and as high as 70 percent for second homes... Loans to property developers are the biggest worry for commercial banks and regulators, but their role in banks’ overall finances is limited... estimated them at 6 to 7 percent of bank lending. China’s banks, with their strong government links, have influence to demand repayment from developers. The other troubled category of customers for China’s banks lies in financial affiliates of local governments, which borrow money on behalf of local governments. The local affiliates have borrowed twice as much from banks as the country’s real estate developers.

Exports have fallen for the fourth straight month, declining 8.8% in August from a year earlier, but smaller than the 14.5% decline in July. Imports too fell by 7.3% over August and 12.4% in July.

Export and import statistics provide one of the early indications each month of how the Chinese economy fared in the preceding month. China relies heavily on running very large trade surpluses every month as a way to create tens of millions of jobs, and that has become particularly important this year as youth unemployment has surged. Exports have become even more important in the past couple years as China confronts a sharp slowdown in the housing market.

The renminbi has hit its lowest level against the US dollar since 2007, having fallen 6% this year so far. The PBoC has a two percent daily trading band on which the currency is allowed to fluctuate.

All these woes are being exacerbated by a crisis of confidence precisely at a time when the economy needs a boost from consumption.

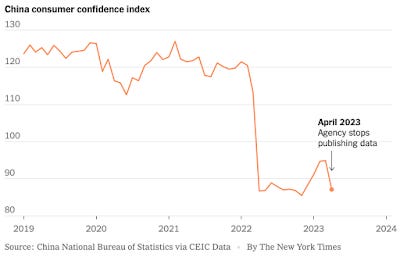

For much of the past four decades, China’s economy seemed like an unstoppable force, the engine behind the country’s rise to a global superpower. But the economy is now plagued by a series of crises. A real estate crisis born from years of overbuilding and excessive borrowing is running alongside a larger debt crisis, while young people are struggling with record joblessness. And amid the drip feed of bad economic news, a new crisis is emerging: a crisis of confidence. A growing lack of faith in the future of the Chinese economy is verging on despair. Consumers are holding back on spending. Businesses are reluctant to invest and create jobs. And would-be entrepreneurs are not starting new businesses... the erosion of confidence was fueling a downward spiral that fed on itself. Chinese consumers aren’t spending because they are worried about job prospects, while companies are cutting costs and holding back on hiring because consumers aren’t spending. In the past few weeks, investors have pulled more than $10 billion out of China’s stock markets.

Adding more grist to the rumour mills, the government also abruptly stopped the publication of important economic data series like that on youth unemployment and consumer confidence.

The usual playbook of loosening the credit spigot to boost lending is unlikely to happen now.

Local governments and businesses are saddled with more debt and less leeway to borrow heavily and spend liberally. And after decades of infrastructure investments, there isn’t as much need for another airport or bridge — the types of big projects that would spur the economy. China’s policymakers are also handcuffed because they introduced many of the measures that precipitated the economic problems. The “zero Covid” lockdowns brought the economy to a standstill. The real estate market is reeling from the government’s measures from three years ago to curb heavy borrowing by developers, while crackdowns on the fast-growing technology industry prompted many tech firms to scale back their ambitions and the size of their work forces.

The Times points to the example of the provinces in the country's manufacturing centre in the Northeast.

In many ways, China’s northeast is a natural target for economic stimulus based on public investment... the northeast still has many multigenerational families of technicians. In the northeast, the manufacturing culture is strong... The region’s iron ore mines, steel mills and machinery factories are little affected by trade issues like the United States’ restrictions on superfast semiconductors... The northeast is home to many state-owned enterprises, some of which have sought greater efficiency by gradually shifting to partial private ownership...

Now the central government, confronting a national economy that has slowed because of a real estate crisis that defies easy fixes, is turning to cities like Shenyang. It hopes to squeeze more productivity and efficiency out of the region’s factories... The region’s birthrate is plummeting: A quarter of the population is 65 or older, and that share is growing about two percentage points a year, while the share of working-age adults is declining by about the same amount. Fewer people are buying new homes, apartment prices are falling and construction cranes are less active. Northeastern China is like the Michigan and Ohio of Chinese manufacturing, but with a population considerably grayer than Florida’s. In many ways, the region is a composite of the most deeply embedded problems facing the country’s economy. The area is heavily in debt. Public revenues are slumping because of the real estate bust. Pensions are the responsibility of the region’s three provincial governments — Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang — and their cost is soaring... As the Chinese economy has slowed this year, the northeast is perilously close to tipping into a recession. Making sure that the economy of China’s industrial heartland can keep growing and support a rising pension burden, as well as produce more exports, has become a top priority in Beijing.

While the central government has fiscal space to indulge in stimulus, they have been reluctant to do so this time. President Xi appears determined to shift away from debt-fuelled policies. This is a good summary of the steps taken till date by the Chinese authorities to address the growing pile of economic woes.

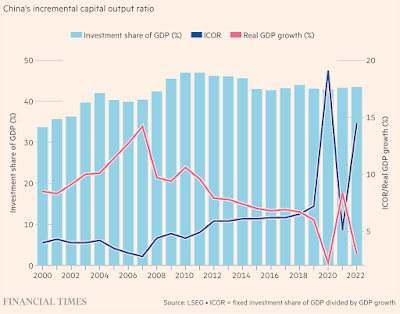

Martin Wolf captures China's economic problem in two graphics. The first points to its over-dependence on investment to generate growth, and its efficiency has been declining over the years.

The second concerns the very low private consumption share of the economy, a share that has hardly budged over the last two decades.

The low private consumption is also driven by the twin effects of a lower share of incomes going to households and a high savings rate among households.

The basic reality of the Chinese economy is that household consumption is only around 40 per cent of GDP. Yes, this is partly because the household savings rate averaged about 35 per cent of household disposable income in pre-Covid years. But it is even more because household disposable incomes are only some 60 per cent of GDP. The other 40 per cent accrues to other institutions, namely, governmental entities, state-owned enterprises and private corporates. The savings rate of these entities appear to have been around 60 per cent of total incomes. That puts the vaunted household savings rate in the shade.

A recent Economist article has this dismal prognosis

Mounting policy failures therefore look less like a new, self-sacrificing focus on national security, than plain bad decision-making... decisions are increasingly governed by an ideology that fuses a left-wing suspicion of rich entrepreneurs with a right-wing reluctance to hand money to the idle poor. The fact that China’s problems start at the top means they will persist. They may even worsen, as clumsy policymakers confront the economy’s mounting challenges. The population is ageing rapidly. America is increasingly hostile, and is trying to choke the parts of China’s economy, like chipmaking, that it sees as strategically significant... China is now testing the... relationship: whether more autocracy damages the economy. The evidence is mounting that it does—and that after four decades of fast growth China is entering a period of disappointment.

FT has another article that points to a subtle shift in Chinese government priorities involving policies that seek to make the market serve the state's strategic interests. Essentially, the government has come to realise the problems with public spending and now is intent on boosting private investment.

President Xi Jinping is intent on boosting investment into sectors that fit with his priorities for control, national security and technological self-sufficiency, and is using stock markets to direct that capital with the aim of reshaping China’s economy... the new approach centres on the top-down co-ordination of resources from government, industry, finance, universities and research labs to accelerate technology breakthroughs and help reduce China’s reliance on the west... Roughly a year ago, Xi told top leaders assembled in Beijing that China needed to mobilise a “new whole-nation system” to accelerate breakthroughs in strategic areas by “strengthening party and state leadership on major scientific and technological innovations, giving full play to the role of market mechanisms”. That “new” in “new whole-nation system”, and the reference to “market mechanisms” distinguish Xi’s vision from that advanced under Mao Zedong, who ruled China from 1949 to 1976. Mao’s original “whole-nation system” entailed Soviet-style top-down economic planning, delivering technological advances including satellites and nuclear weapons, but not prosperity for the masses...

Whereas Mao shut down China’s stock exchanges, Xi wants to use domestic equity markets to reduce dependence on property and infrastructure development to drive growth. But his “new whole-nation system” prioritises party policy above profit. This helps explain why the party’s top cadres have been fast-tracking IPOs but remain reluctant to deploy large-scale property and infrastructure stimulus to reinvigorate economic growth. In their eyes, returning to the old playbook would only postpone an inevitable reckoning for debt-laden real estate developers and delay the planned transition to a new Chinese economy. Key to that shift, Goldman’s Lau says, is getting companies in sectors such as semiconductor manufacturing, biotech and electric vehicles to go public. With stock market investors backing them, they can scale up and help drive the growth in consumer spending needed to fill the gap left behind by China’s downsized property market.

This has involved encouraging private firms to get listed in the markets through IPOs, steering private venture capital into critical sectors, channel domestic savings through equity markets to prioritised companies, etc. This is an interesting example of the kind of top-down micromanagement that's going on to co-ordinate capital market activity,

Xi’s administration was already channelling hundreds of billions of dollars from so-called government guidance funds into pre-IPO companies that served the state’s priorities. Now it is speeding up IPOs in Shanghai and Shenzhen while weeding out listings attempts by companies in low-priority sectors... a behind-the-scenes “traffic light” system, in which regulators instruct Chinese investment banks informally on what kinds of companies should actually list. Companies such as beverage makers and café and restaurant chains get a “red light”, in effect prohibiting them from going public, whereas those in strategically important industries get a “green light”... a director at one large Shanghai-based brokerage says officials are clearly “trying to push those strategic sectors like high-tech manufacturing, renewables and other new economy-related industries to list and raise capital and flourish.” Listings in those sectors proceed quickly while those companies that do not align with policymakers’ priorities find themselves without the investment bank backing needed to go public...

This approach could run into difficulty if shares in those companies going public are sold down immediately by investors hoping to cash out at a profit when prices rise appreciably in the first few days of trading. Regulators have guarded against that risk by extending “lock-up” periods, during which Chinese investment banks and other institutional investors who participate in IPOs are not permitted to sell stock... Regulators have also restricted the ability of company insiders — be they directors, pre-IPO backers or so-called anchor investors — to sell their shares, especially if a company’s shares fall below their issue price or it fails to pay dividends to its shareholders. The day after these changes were announced, at least 10 companies listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen cancelled planned share disposals by insiders. An analysis of the new rules’ impact by Tepon Securities showed that almost half of all listed companies in China now have at least some shareholders who cannot divest.

But such micromanaged co-ordination has its limits. For example, the flood of new listings has dragged down the market as investors sell their existing shares to raise money to buy new shares. This in turn has made the authorities force domestic institutional investors to buy and hold shares in strategic sectors to prop up the market.

The latest such move came earlier this month, when China’s insurance industry regulator lowered its designated risk level for domestic equities in an attempt to nudge normally cautious insurers to buy more stocks. Such measures show that Xi’s stated plan to give “full play” to the role of markets comes with an important rider: those markets will take explicit and frequent direction from the party-state... the enhanced role of the state in China’s stock markets... Last month, offshore investors trading through a market link-up between Hong Kong and mainland bourses sold a record $12bn of Chinese equities, according to Financial Times calculations based on stock exchange data. Fund managers say the country is in the middle of a structural derating, whereby international investment funds permanently reduce the proportion of capital they judge prudent to allocate to China’s stock market. That undermines longstanding efforts, including initiatives launched early in Xi’s tenure, to persuade foreign fund managers to take up larger positions in Chinese companies. Back then, the belief that international capital would help dampen share price volatility — largely stoked by the country’s trend-driven retail traders — helped push pro-market reforms that resulted in Chinese securities being included in the global benchmarks used by large index-tracking funds. Now, as foreign funds are dumping their holdings, traders and strategists say China’s “national team” of state-run investors is busy buying in as part of an effort to prevent a more serious market rout... investors are warning that the ever-expanding system of state controls over equity investment could do lasting damage to Chinese stocks’ domestic and global appeal.

Besides such policies can have a knock-on impact on the economy

Economists say that the tech sectors being favoured for listings by Beijing — semiconductors, EVs, batteries and other high-end manufacturing — are simply not capable of providing the scale of employment opportunity or driving the levels of consumer spending anticipated by top Chinese leaders. “There’s two problems with focusing on investing in tech,” says Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University and senior fellow at Carnegie China. “One is that tech is very small relative to what came before [from property and infrastructure], and two is that investing in tech doesn’t necessarily make you richer — it’s got to be economically sustainable”... If Chinese equities continue to lag other markets over the long term, that could start to weigh on household spending and further hobble growth.

Despite the crisis, the government appears reluctant to address the elephant in the room - the country's disproportionately low share of private consumption. The Times points to the failure of the Chinese authorities to encourage consumption by increasing the country's social safety net.

Western economists have long contended that the answer to China’s economic troubles lies in reducing the country’s high rate of savings and investment and encouraging more consumer spending... But China has done little to strengthen its social safety net since then, so that households would not feel a need to save so much money. Government payments to seniors are tiny. Education is increasingly costly. Health care insurance is mostly a municipal government responsibility in China, and high costs for the strict “Covid zero” measures the country employed have nearly bankrupted many local government plans...

China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, has a well-known aversion to any social spending, which he has derided as “welfarism” that he believes might erode the work ethic of the Chinese people. “Even in the future, when we have reached a higher level of development and are equipped with more substantial financial resources, we still must not aim too high or go overboard with social security, and steer clear of the idleness-breeding trap of welfarism,” Mr. Xi said in a speech two years ago.

Beijing has just recently belatedly intervened to address the economic distress. Signaling its intent to support the currency, the PBoC has reduced from 6% to 4% the amount of foreign currency that financial institutions are required to hold in reserve. To support the housing market, minimum mortgage interest rates for first-time home buyers were lowered by the cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen. This follows decisions to reduce the minimum downpayment requirement for first and second-home purchases and to cut interest rates for existing mortgages.

These policies are mostly cosmetic in nature and may point to confusion within the establishment. The government was initially determined to prick the bubble and bring discipline to the real estate sector. But now appears to be caught in two minds given the intensifying crisis.

The failure to intervene to address the snowballing crisis is only the latest in a series of bad policy choices by President Xi Jinping since 2020. The crackdown on the tech sector and moral policing has spooked investors and entrepreneurs, including the domestic ones. The zero-covid policy was an unmitigated health care and economic disaster. The three redlines policy of abruptly tightening the real estate market after years of permissiveness may have been the trigger for bringing down a sector that contributed nearly 30% to the economic output. Then there have been omissions by way of failing to act on rebalancing the economy away from investment towards consumption, shoring up the social safety net, diversifying away from real estate sales and nurturing alternative revenue sources like property tax, reforming the urban hukou system, etc.

The combination of hastened salami-slicing policy on border conflicts with neighbours and uncouth wolf warrior diplomats running roughshod have alienated neighbours and important trade partners. Such aggressive foreign policy posturing, tightening restrictions on foreign companies operating in China, and cases of espionage involving strategic sectors have unleashed a full-blown Cold War with the US. All this has been exacerbated by the centralisation of power with the President, cracking down on dissent, packing of the government and party with loyalists instead of technocrats, and the general elevation to the supremacy of Xi Jinping over the Communist Party.

The safety valves within the Communist Party and the Government have been tightly shut. The wisdom of feeling the stones and crossing the river has been replaced by top-down policy-making administered through loyalists. All this is par for the course for the latest version of China's Bad Emperor problem who has swept aside the wise strategy followed by his predecessors and threatens to not only ruin his country's progress but also create geopolitical tensions.