Greedflation - it's not wages, but profits!

The aftermath of the pandemic and the subsequent economic recovery has raised several questions. Arguably the most salient has been the search for explanations for the rising inflation.

The immediate and most widely discussed explanation was the wage-price spiral - where wages pressures upward entrench inflation. This was corroborated by the labour market tightness as the pandemic restrictions eased and demand rocketed. There were some signs that this was leading to higher wages.

Economists and commentators were quick to point to wage-price spiral and express concern at labour's rising bargaining power. Central bank governors, chief executives, and important opinion makers were constantly on newspapers and television channels arguing on the need to contain the wages growth. Andrew Bailey the Governor of Bank of England called for pay restraint by workers.

But there is now some evidence to question this claim since inflation has outstripped wage growth for 22 consecutive months.

There is another interesting trend, which appears to point to the possibility of a profit-maximisation-price-markup spiral. There has been the spike in business margins and profits of the biggest firms, despite the supply shocks from the pandemic, Ukraine wars, and Chinese lockdowns, and its contribution to the high inflation. Now there is increasing evidence that business concentration and associated price markups may be contributing to inflation. Unsurprisingly, this has not generated anything remotely close in terms of public commentary and calls on corporates for restraint on their price markups.

The spike in profits of non-financial corporates after the pandemic has been stark.

The companies passed on the higher cost of production

Companies passed these higher input costs on to their clients, and then went further: margins reached record highs. Earnings before interest and taxes peaked in the course of 2022 at nearly 18 per cent of revenues on average for the largest US listed companies and more than 15 per cent for Europe’s biggest listed groups, according to data compiled by Refinitiv.

Profit margins at public companies in the eurozone — measured by net income as a percentage of revenue — averaged 8.5 percent in the year through March, according to Refinitiv, a step down from a recent peak of 8.7 percent in mid-February. Before the pandemic, at the end of 2019, the average margin was 7.2 percent.

Economists Isabelle Weber and Ivan Wasner have even documented evidence that these price pass throughs have fed into the inflationary pressures.

We argue that the US COVID-19 inflation is predominantly a sellers’ inflation that derives from microeconomic origins, namely the ability of firms with market power to hike prices. Such firms are price makers, but they only engage in price hikes if they expect their competitors to do the same. This requires an implicit agreement which can be coordinated by sector-wide cost shocks and supply bottlenecks. We review the longstanding literature on price-setting in concentrated markets and survey earnings calls and compile firm-level data to derive a three-stage heuristic of the inflationary process: (1) Rising prices in systemically significant upstream sectors due to commodity market dynamics or bottlenecks create windfall profits and provide an impulse for further price hikes. (2) To protect profit margins from rising costs, downstream sectors propagate, or in cases of temporary monopolies due to bottlenecks, amplify price pressures. (3) Labor responds by trying to fend off real wage declines in the conflict stage. We argue that such sellers’ inflation generates a general price rise which may be transitory, but can also lead to self-sustaining inflationary spirals under certain conditions. Policy should aim to contain price hikes at the impulse stage to prevent inflation from the onset.

ECB officials have stated that in the fourth quarter of last year half of domestic price pressures in Eurozone came from profits, with the other half from wages. But while wage growth has received all the public commentary, profits growth has been overlooked by academics and commentators.

As a recent paper by New York University economist Viral Acharya has found rising business concentration translating into higher price markups in the Indian economy, which got pronounced in the aftermath of the pandemic. They use data on Indian non-financial firms to estimate price markups by using the product price changes for a 1% change in input cost of the firm. They analyse the data to make the distinction between the respective impacts of the Big Five firms (Reliance, Tata, Aditya Birla, Adani, and Bharti) and the Top Five in an industry in any year.

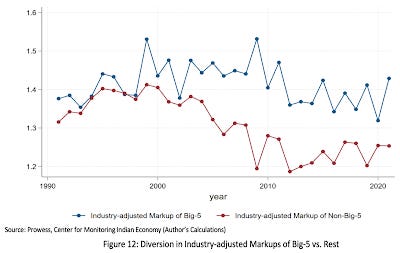

Markups fell gradually from early 1990’s until 2013, but started rising steadily and significantly thereafter, scaling in 2021 the high level of 1.4 in 1990’s, and even when capacity utilization in the Indian industry was low during the pandemic due to collapse of aggregate demand... we find that there is a potentially causal link from market power to markups. To illustrate the econometric results visually, Figure 12 shows the industry-adjusted markups of Big-5 and the rest, establishing a persistent and substantial 0.1-0.3 (i.e., 10-30 percentage points) markup gap between the two groups over the past two decades.

Interestingly, there is no such robust pattern in Figure 13 for Top-5 firms in each industry in a given year (as explained earlier, Top-5 in a given year overlap but do not fully coincide with the aggregate Big-5). In other words, it is the Big-5 which are able to exert extraordinary pricing power and capture economic rents relative to other firms in the industry, whereas Top-5 but non-Big-5 firms in a sector are not associated with such an outcome in markups.

It gets even more specific since Acharya also finds that the Big-Five might be responsible for contributing to inflationary pressures

Further evidence suggests that, in keeping with the rest of the results, lagged sales share of Big-5 groups in an industry feeds into its wholesale price inflation in a year, whereas the lagged share of Top-5 groups does not, with a 10% rise in Big-5 share within an industry associated with a 2.7 percentage point higher WPI inflation next year.

I have blogged earlier that the incentives that underpins capitalism and the enabling regulatory and market structures creates a dynamic of business concentration and profit maximisation among the top firms. This is almost an iron law. The result is market power and higher markups. This figure is a good illustration.

This has naturally promoted calls for government intervention, including some form of price controls. I'm not sure that's the right way since not only does interventions like price controls engender distortions and perverse incentives, they also do not address the central problem of business concentration and the financial incentives and political economy associated with it. As I have blogged earlier here, here, here, and here, more than its immediate economic consequences, it's the political capture of rule making by large firms that is the big problem facing capitalism today.

Underlining the point, in the context of the bailout of the Silicon Valley Bank, whose main beneficiaries were the big technology companies, Ruchir Sharma pointed to this in a recent oped,

In Texas, the mayor of Fort Worth recently said that the “main thing” worrying business leaders is this question: if SVB had served the oil industry rather than tech, would the government “have stepped up the same way?”

There are no easy answers here. The simplest response of breaking up large firms simply because they are large is fraught with problems, though that will invariably be the final outcome. A more nuanced approach would be to go back to first principles and strictly apply the regulatory tests of entry barriers, anti-competitive practices, conflicts of interests etc to determine whether the firm's practices are causing market harm and hurting consumer welfare, and then force unbundling or regulatory barriers on the emergence of restrictive market structures. Fortunately some steps in this regard is already underway on both sides of the Atlantic (here and here). But the resistance from the entrenched interests will be very strong and they will be supported by their captured political bidders.