The rise of industrial policy globally naturally raises the question of which instruments generate the greatest value for money. This post will examine the case of public funding of startups engaged in technology innovation.

Thomas Hochman has a long read in American Affairs which compares the instruments used by the CHIPS and Science Act and the IRA Act.

The… CHIPS and Science Act, works mostly through grants: funding awards are given directly to specific manufacturers by the Department of Commerce, with explicit terms around domestic production, intellectual property sharing, and reinvestment of profits. This has its benefits: the spending is easy to track, is highly targeted, and carries little risk of filtering out to foreign adversaries… But there are downsides to this approach. Direct government spending requires administrative capacity: the federal, state, or local agency responsible for carrying out the program must solicit applications, review them, and make decisions about whom to award money. It also requires organization on the part of private sector applicants, who often lack the resources and know-how to put together grant applications in the first place, or even to gain awareness of relevant programs’ existence.

The result is that grants tend to roll out slowly. At the time of this writing, almost two years since the passage of chips, less than $1 billion of the $52 billion appropriated for semiconductor funding has been formally awarded… Similarly, the $5 billion National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program, passed through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in 2021, has led to exactly eight charging stations being built as of February 2024, while hundreds of other years-old federal spending programs have yet to make a single award.

The Biden administration’s second philosophy of industrial policy is exemplified by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA takes a climate-first approach, prioritizing emissions reductions over China competition, with the goal of deploying as much clean energy infrastructure as quickly as possible. Accordingly, the law works through “as-of-right” tax credits: companies that meet certain eligibility requirements can claim the credits, incentivizing clean energy investment while creating relatively little bureaucratic friction. The upshot is that IRA funding has reached the clean energy industry much more quickly than CHIPS funding has reached semiconductor firms. But this approach has its drawbacks as well. Whereas grant programs lack speed, tax credits lack transparency. Because as-of-right tax credits are facilitated through the tax code, they are protected by Internal Revenue Service confidentiality. As a result, no one—not the public, nor watchdog groups, nor even most members of Congress—knows exactly how much we’re spending, when we’re spending it, and on whom we’re spending it.

The essay points to the economic inefficiency associated with tax credits, especially with tax credits that are allowed under the IRA Act to be transferred to unrelated third parties, tax-free. It highlights the example of Ashtrom Renewable Energy, which expects to generate around $300 million in production tax credits over ten years from its 400 MW solar project in Texas. It immediately sold its entire $300 million credits to a financial institution with sufficient tax liability to offset its taxes over ten years.

Tax equity investors appear to be syndicating portions of their credits, and dedicated brokers and insurers are emerging to facilitate trades. These middlemen are seeking to maximize their own returns, of course, and their cut ultimately reduces the amount of public money reaching actual projects. There’s also the simple fact that if tax credit recipients pursue transferability, then the credit is not worth its full dollar value to the seller. The upshot is that the IRA credits are being transferred at an average of about 93 cents per dollar of credit value—in other words, at a 7 percent loss in credit efficiency… Indeed, the cost of monetizing credits through the tax equity market can be as high as 15 percent of the credits’ value… Reports from intermediaries suggest that the institutions that have historically been involved in tax credit deals are the same ones buying up IRA credits today: banks, insurance companies, and other major corporate taxpayers. This is not to mention the benefits to the many syndicators, tax advisers, and insurers that have emerged in the wake of the IRA’s passage, all of whom are skimming cents off the top of every dollar of credit value.

The essay concludes by pointing to the advantages of grants

Grants have been a staple of U.S. industrial policy for decades, from the Advanced Research Project Agency’s funding for energy R&D to the Department of Defense’s defense industrial base grant program. And while grants often involve more bureaucratic processes compared to tax credits, they offer several advantages. First and foremost, grants provide greater up-front control and ability to target funds strategically… grants allow for more due diligence and selection of recipients aligned with those strategic goals. Policymakers can target specific industries, technologies, or geographic areas, and put in place guardrails to prevent funds from benefiting foreign competitors.

Grants also offer enhanced transparency and accountability compared to tax credits. While tax credit data is shrouded in IRS confidentiality, grant recipient information is typically public… Third, grant agreements provide an opportunity to set specific conditions and requirements for recipients. Agencies can specify the scope of work, set milestones and reporting requirements, and include clauses to suspend or reclaim funds if conditions aren’t met… For all of these reasons, grants are particularly well-suited for advancing national security priorities and shoring up strategic industries.

This debate has relevance for India. Apart from the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme aimed at encouraging domestic manufacturing in general, several Departments of the Government of India and state governments are implementing industrial policy to promote innovation in cutting-edge industries. In the last Union Budget, the Government of India announced a Rs 1 trillion funding pool to spur private sector-driven research and innovation, including a Rs 100 million VC fund to invest in innovation in the Space sector.

The case for direct public funding of innovation through research and development (R&D) by public institutions is not under dispute. So also is that for tax concessions to private sector investments in R&D. But there’s a challenge with public funding of startups involved in technology innovations. What’s the appropriate mechanism to do such early-stage funding?

For a country like India, there’s a strong economic and strategic imperative to encourage entrepreneurship in emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, quantum computing, cyber security, 5G and 6G telecommunications and its use cases, EV battery chemistry, green hydrogen production, etc. While the country has witnessed a sharp rise in venture capital investments, a very tiny proportion has gone to these cutting-edge technologies. There’s a strong case, therefore, for governments to step in and address the market failure by financing startups involved in the prioritised sectors. Barry Naughton describes here how the Chinese have gone about it.

Traditionally, public support for startups has been to establish incubators and provide space and shared services. While that remains the situation, a few governments are tentatively venturing into financing startups engaged in innovation.

In theory, such startup financing can come as grants, or debt, or equity. But debt is not considered appropriate for startups since they are unlikely to be able to generate requisite cashflows in the foreseeable future to meet the loan repayment obligations. And as the article above informs, while grants are simple to implement, they come with administrative delays. In addition, grants have an incentive compatibility problem.

For this reason, it’s argued that public support to support innovation should be as equity. Since making equity investments requires good due diligence and portfolio management capabilities, it’s also argued that equity investments should be made through arms-length entities with professional investment managers. Besides, equity investments directly by government entities create insurmountable legal issues and are vulnerable to being abused.

Given all the aforementioned, how do governments support startups in prioritised sectors?

As a starting point, the funds must be routed through an arms-length entity. Government departments themselves or units housed within departments should not be making grant approvals. The appropriate entity can be a society or a company, depending on the instruments proposed to be deployed.

The choice of instrument is more complicated. It’s natural to be attracted by the venture capital (VC) model and replicate it with public funds. There are several challenges with this approach. For one, to avoid public oversight agencies (with all the accompanying risk aversion it induces), like the National Infrastructure and Investment Fund (NIIF), the entity must have a majority of private shareholders.

But, if a NIIF-like entity is merely blending public and private funds instead of offering public funds as a concessional layer, it’s unlikely to serve the purpose. For a start, there’s little by way of de-risking achieved by the public funds deployed. Second, since public funding of startups is necessitated by the market failure in the supply of private capital, this entity is unlikely to make many investments.

It’s for this reason that NIIF has struggled to make any headway in genuinely de-risking infrastructure projects and has instead become just one more infrastructure investor in the market. The de-risking objective of public funds will invariably get squeezed out by the returns maximisation objective of private capital in any entity where private shareholders are a majority at the asset management company level.

Instead, if public funds are blended as concessional capital through co-financing by a wholly government-owned entity, its administration will be fraught with problems. The nature of the instrument used and the degree of concessionality provided will need to be determined on a case-by-case basis, thereby making it excessively subjective and inviting public scrutiny and associated controversies. This possibility invariably creates risk aversion.

Further, being early-stage firms, the amounts proposed to be disbursed are small. Since equity investments demand a certain level of legal, governance, and financial due diligence, the due diligence-related transaction costs for smaller equity investments are disproportionately high, even prohibitive.

The option of having an entity which is fully owned by the government and using public funds to undertake equity investments also cannot avoid the accompanying rigorous public oversight. This creates problems since the entity will be making genuinely risky investments, and the vast majority of them will fail. Hindsight-based scrutiny of such investment decisions can be fraught with recriminations. Traditional public oversight and VC-type investments cannot go together.

Further, given the constraints of a purely publicly financed entity, it’s tough to recruit and retain the minimum complement of a competent team of investment professionals to do due diligence (supplemented with a panel of external experts) on the investments, approve them, and undertake even light-touch portfolio management activities.

In these circumstances, the most effective public policy instrument to support innovations would be conditional grants with clawback provisions. As mentioned earlier, grants are easy to target and can be structured with conditions, including recovering them in full or partially if the startup succeeds commercially. The CHIPS Act has provisions that require the sharing of any upside beyond a certain level with the government. Similar upside-sharing provisions exist in all the innovation-focused funding across Europe. Besides, unlike equity or debt, grants are easier to administer for both the grantee and grantor.

Finally, grants with upside-sharing provisions offer a win-win proposition to both entrepreneurs and governments. It leaves start-ups without any immediate repayment liabilities, especially attractive in the early days of a startup pursuing risky innovations. It offers governments the possibility of being able to recover the grant partially or fully. In other words, grants with clawback are both incentive-compatible and provide the most cost-effective derisking.

The entity could prioritise its portfolio management role by bringing together panels of investors, industry leaders, and academic researchers to advise and mentor its grantees. It could have partnerships with VC and other investors to connect its grantees with those looking for good investment opportunities. Being government-owned, it could facilitate various government-related approvals and permissions and also help with leveraging any other support from the government for the startups.

Given the significant amount of fiscal benefit being provided to individuals/firms, grantmaking must have reasonably rigorous due diligence and governance requirements. Also, given the difficulty of attracting high-quality talent, the in-house team should be combined with a standing panel of reputed subject experts drawn from academia, industry, and the investment world to conduct due diligence on grant applications.

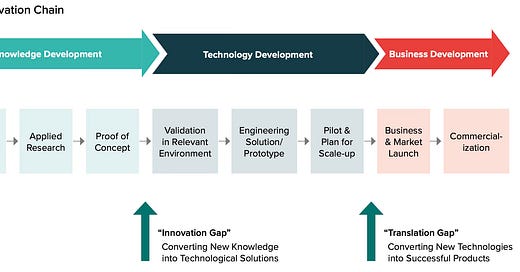

The technology readiness levels (TRL) for which the investments are eligible should be clearly defined, with the corresponding upper limits for the grant amounts. There should be follow-on grant provisions for exceptionally promising innovations but with higher-level approval. A good practical framework to figure out which stage of innovation is appropriate for funding is below.

There should be standardised checklists and templates for the due diligence of the innovation and its technology, the business model, the entrepreneur, the legal issues, etc. Due diligence should involve 2-3 screenings, with the final short-listed applications subjected to reasonably rigorous scrutiny. The processes should be workflow-automated and high standards of governance followed. A high-level committee should periodically review the grant-making process, the pipelines created, the portfolio management activities, and the health of the grantee startups.

Such grant-making can be supplemented by offering public funds as a concessional layer to mission-aligned private investment funds with certain light-touch conditions on the destination of the funds. This fund-of-funds approach is easier to administer, given the limited number of transactions. Besides, it enables the recipient funds to more effectively de-risk their investments, thereby expanding their universe of investible startups and crowding in more private capital.

Update 1 (29.01.2025)

On UK universities and their commercial startup spinouts.

Universities, founders and investors clash frequently. All would agree that value resides in intellectual property, but where the IP itself resides is a knottier issue. At Cambridge, the university gets first dibs. Compare that with Sweden’s Uppsala University, which usually confers ownership on the originator. One case, involving the University of Oxford, wound up in court. That is just one hurdle. Extricating spinouts can be laborious; academia moves slowly. As the UK government’s 2023 review noted, panels are composed of committees that only meet irregularly and lack commercial experts. The average spinout took 10-12 months; for 16 per cent it was more than 16 months. Universities are reluctant to cede much of their innovations: one in four spinouts began negotiations demanding a 50 per cent equity stake. Investors balk at being accorded just crumbs. This is improving — the average university equity stake at spinout fell to 18 per cent in 2023, from 25 per cent a decade ago — but there is scope for further loosening of the reins.