The private equity transformation of capitalism

Capitalism is undergoing a quiet transformation as institutional private capital increases its ownership footprints across vast swathes of the economy. What are its implications?

John Gapper in FT has an excellent article highlighting the journey of Pimlico Plumbers, a family-owned plumbing and home repair service founded in 1979 by Charlie Mullins, and which was sold three years back to US home services platform, Neighbourly, owned by the PE firm KKR for £140 mn. The firm distinguished itself by the reliability and quality of its service and charged a high hourly rate to well-off customers.

Pimlico was a pioneer of charging well-off customers a higher hourly rate for reliability. Instead of plumbers who turned up late if at all, and exploited their customers’ ignorance of home piping to overcharge, Pimlico offered a consistent service from uniformed engineers who were polite and cleaned up their mess afterwards. It was a simple formula, but someone had to reform a fragmented, opaque cottage industry and Mullins was the innovator. Private equity has now seen its own opportunity, having rolled up family-owned veterinary and dental practices. Brookfield Asset Management struck a £4bn deal in 2022 to acquire HomeServe, the UK home repairs cover group. As family founders of home services companies approach retirement, investors want to increase the scale of the industry, while maintaining quality.

The article informs that the Mullins family (of three generations) are now going back to their business after the expiry of a three-year non-compete clause by launching a new home service firm, WeFix.

WeFix bears all the hallmarks of his formula for Pimlico: a call centre on the premises, vans waiting to be cleaned and valeted, a space for apprentice training. It will squarely target the same group of customers… If anything, it will be more elite: the new business plans to charge £180 an hour for daytime jobs, compared with Pimlico’s £125 hourly minimum for plumbing. This will enable its top engineers, classed as self-employed with some workers’ rights after a 2018 Supreme Court ruling involving Pimlico, to earn between £150,000 and £200,000 per year... The family has become a dynasty, with 15 members, including partners, now involved in WeFix. Scott is chief executive and Ashley managing director; Charlie has no stake, but the company is infused with his philosophy. Scott compared its approach to personal service with the luxury department store Harrods: “You know the prices, you know the quality, you know you’ll be looked after.”

But while they have high ambitions for quality, they are modest about WeFix’s potential size. They are keener to replicate and refine the old Pimlico model than to extend it further. Charlie said that Pimlico had about 250 engineers when he sold it — many more than the average home services business — but standards had been slipping. “We took on some people who were not up to our standards. We fell into the trap of growing too fast because demand was so high,” he said. They intend to proceed more slowly this time, aiming ultimately to reach about the same size as Pimlico. WeFix London will not expand beyond the city: the family feels most comfortable on its home turf.

Interestingly, Charlie Mullins, the founder and patriarch, does not think the PE model will work in the business.

A family business is more personal, more caring, we put more into it.

The case study points to an important and less appreciated trend in the economy, especially pronounced in the United States.

Historically, most of the regular consumption services for households and offices were provided mainly by small family-owned shops (mom-and-pop shops) and small businesses. They include clinics and hospitals, pharmacies and diagnostic facilities, schools and colleges, bars and restaurants, old age homes and terminal care services, security, home repairs and other services, office services, personal care (salons, beauty and cosmetic centres, nails etc.), veterinary care, local sports teams, and so on.

Now, after establishing their dominance in finance, technology sectors, startups, real estate, infrastructure etc., PE firms are expanding into these markets. They realise that these market segments that serve people’s daily lives offer low-risk and stable revenue opportunities. No matter what happens, good times or bad, there will always be stable demand for these goods and services. They are the so-called essential services with very low elasticity of demand.

There are at least three concerns I have with the rise of PE firms in these business areas. Is it the right kind of capital to finance these activities? Can they offer the kind of quality of service that many of these activities require? Can they ensure the kind of responsibility to its customers, workers, and communities that local or public capital provides?

In the spectrum of financial intermediation (compared to debt, personal financing, and public equity), PE firms provide equity and represent high-net-worth individuals (and increasingly institutions). By its very nature, it’s capital with high risk appetite and searching for high returns. Further, the high fees demanded by its managers, add to the returns expectations. Can the kinds of essential services like those mentioned above command the sort of margins to justify these return expectations?

If not, then the only way the returns will be generated would be by asset stripping and squeezing the firm’s cash inflows and passing the parcel till it becomes insolvent. The incentives of the PE fund managers and investors are aligned towards pursuing such practices. This blog itself has documented several examples from recent times of such practices.

Most of the services of the kind mentioned above demand some form of personal connect. The family-owned provisioning of these services provided some neighbourly personalised touch that disappears with the distant ownership by PE investors and their fund managers. The PE fund managers invariably rely on the standard approach of giving targets for the number of customers served and their unit efficiency of service, and minimising the cost of this service delivery while maximising the prices. It’s impossible to do all this and also maintain quality and the personalised care.

Finally, the nature of the PE ownership almost eliminates any fiduciary relationship between the company owners and its customers, employees, and communities. The single-minded pursuit of cost minimisation and profit maximisation leaves both customers and employees worse off. The diffused ownership, portfolio approach of PE funds, and their outsourced management also mean that the PE firm can cut losses and exit a company with fewer restraints and costs.

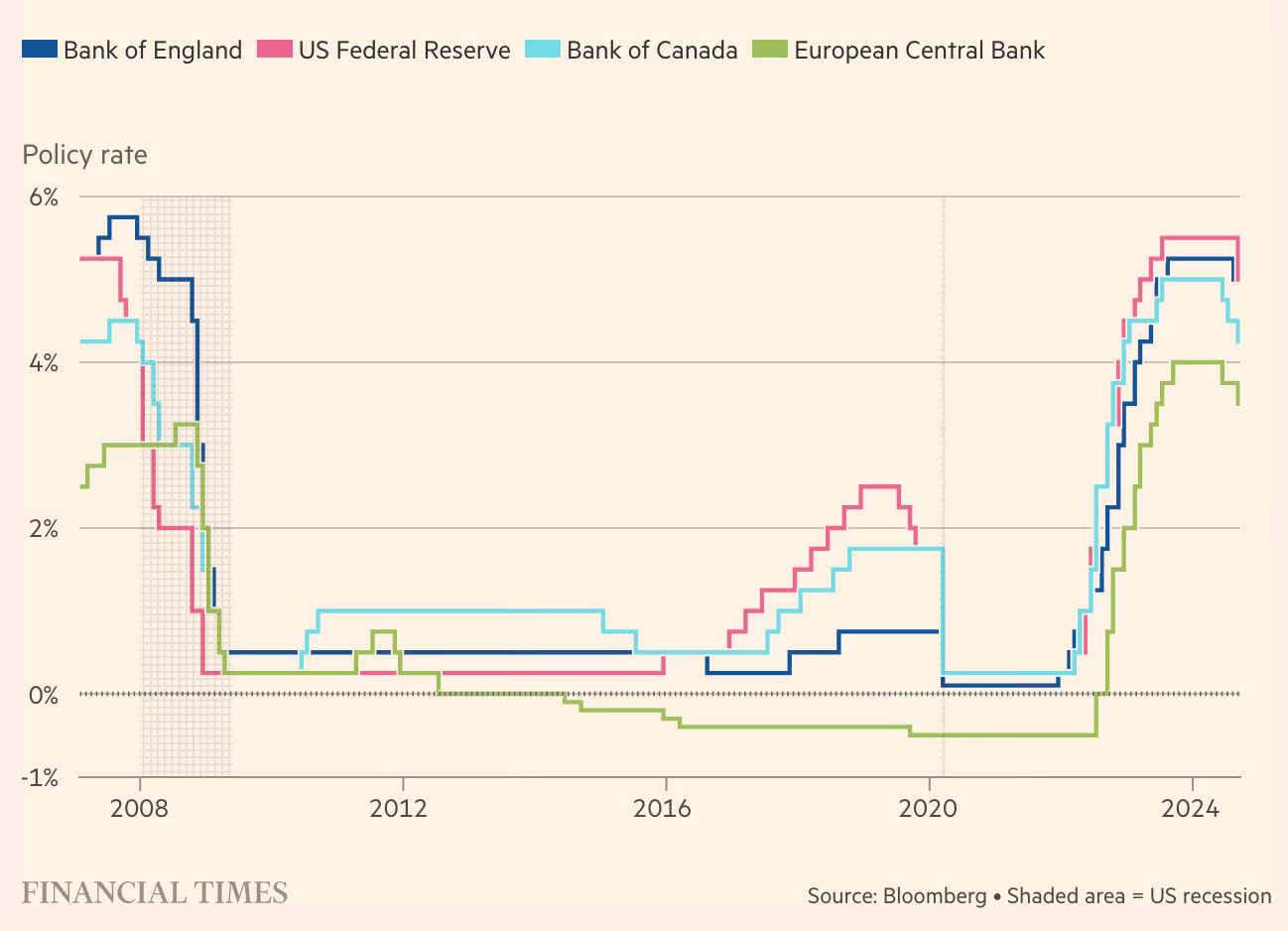

As to what’s driving this kind of capital, I can think of two important contributors - ultra-cheap capital and regulatory arbitrage. Since the Global Financial Crisis (or perhaps since the turn of the millennium), barring limited periods, the advanced economies led by the US have experienced extraordinary monetary accommodation by central banks.

The low interest rates were a big boost to the PE business model that relies on extensive use of leverage to juice up returns. It also allowed PE firms to attract massive volumes of capital from both wealthy individuals and institutional investors (searching for yield in times of low fixed-income returns), which in turn found its way into these newer and stable return market segments.

Spurred by imperatives like financial market regulation, trade standards, and addressing climate change, governments have become more invasive over the last two decades in terms of regulations and compliances. Accordingly, the costs of being a small business (and a public limited company) have steeply risen whereas the advantages of being a privately held company have increased just as sharply. This attractive regulatory arbitrage opportunity even incentivizes firms to remain private and exit the public markets.

As long as PE was confined to a few sectors and its investors were just ultra-high-net-worth individuals, it might have been all right to allow light-touch regulations. But with PE ownership expanding its roots across the economy and with institutional investors like pension funds and insurers contributing an increasing share of PE investments, there’s a greater case for regulation of PE firms on similar lines as public capital. In fact, with an increasing share of capital from tightly regulated institutions, it may no longer be appropriate to even describe PE as private capital.

Update 1 (27.09.2024)

The latest example of how PE firms use leverage to finance dividend payouts and leave the companies deeply indebted and vulnerable to bankruptcy.

A company backed by Clayton, Dubilier & Rice and Hellman & Friedman, BlackRock and GIC is preparing one of the largest debt-fuelled dividend payouts in private equity history… Belron, the world’s biggest windscreen repair company, is in talks with lenders to raise €8.1bn through new bonds and loans. It plans to use the cash to pay a €4.4bn dividend to an investment group that includes the private equity firms, asset manager and Singaporean sovereign wealth fund… Belron, which owns the Safelite brand in the US and Autoglass in the UK, is half owned by listed Belgian conglomerate D’Ieteren Group. The distribution is the largest recent debt-funded dividend payout attempted by a private equity firm, surpassing payouts made to buyout firms by office supply store Staples, European home security giant Verisure and railroad Genesee & Wyoming… Analysts at credit rating agencies Moody’s and S&P Global downgraded Belron deep into junk territory this week… One person involved in the Belron loan offering said it was the largest such transaction they could find in their records dating back more than a decade. The dividend will nearly double Belron’s overall debt from less than €5bn to almost €9bn. The ratio of its debt to ebitda will jump to about 5.8 at the end of the year from 3.3 in 2023, according to S&P.

The Belron dividend payout has an interesting context that shines light at the PE business model.

The billions of euros expected to be paid to Belron’s owners will generate large early returns for a closely watched transaction struck at the apex of a dealmaking boom in 2021 when private equity firms were paying high prices to buy businesses. CD&R bought a 40 per cent stake in Belron from D’Ieteren at an €3bn valuation in 2018, but cashed out of its initial investment in a complex 2021 deal that valued the windshield repair company at a staggering €21bn, seven times what it had paid three years earlier, as operating profits surged. But CD&R was keen to maintain an investment in the business, and it created a special fund known as a continuation vehicle to buy part of Belron from its flagship private equity vehicle. CD&R Value Building Partners, the new fund, bought a stake of more than 20 per cent stake in Belron, while H&F, GIC and BlackRock collectively bought a stake of more than 15 per cent which helped to validate the valuation. If the dividend-deal is completed, investors backing the company in the 2021 deal will have had 35 per cent of their original capital returned through dividends, according to two sources briefed on the matter, without having sold down any of their investment. Those returns would make Belron an outlier from among a record wave of private equity deals struck in 2021 where little capital has been returned.

The above example comes even as FT reports of PE firms pushing the boundaries on how much they can takeout from their investee companies by creative accounting interpretations.

Private equity firms are aggressively pushing to include language in loan documents that could give them room to pay themselves larger dividends from the companies they have bought, drawing a sharp rebuke from lenders. In the past, loan documents usually capped exactly how much money a private equity firm could extract from one of its portfolio companies. Over time, those fixed amounts became malleable and were based on a percentage of a company’s earnings. But in recent weeks, private equity firms have been attempting to take things one step further with the so-called high-water ebitda provision, which allows a company to use the highest earnings it generates over any 12-month period for critical tests that govern how much debt the company can borrow or the size of dividends it can pay to its owner, even if the business’s earnings have slid since reaching that high point. KKR, Brookfield, Clayton, Dubilier & Rice and BDT & MSD Partners have all attempted to work the clause into loan documents.

Update 1 (10.11.2024)

Veterinary care has become the latest in the sectors dominated by independent businesses to fall to private equity investments.

Private equity groups Silver Lake and Shore Capital Partners have struck a deal to create one of the biggest US veterinary care groups valued at $8.6bn, with ambitions to further consolidate a sector historically dominated by independently-owned businesses, said people briefed on the matter. The merger between Southern Veterinary Partners and Mission Veterinary Partners, both of which were part-owned by Shore, will create a network of vet hospitals and clinics spanning more than 750 locations and generating $580mn in yearly earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation. The veterinary sector is benefiting from a surge in demand as people seek care for their animals following a pandemic boom in ownership... As part of the deal, Silver Lake and Shore Capital will make a $4bn fresh equity investment split evenly between them... People briefed on it said the combined company is likely to pursue more deals to roll up vet clinics and hospitals, as private equity groups play an increasingly dominant role in consolidation sweeping the petcare industry... Bloomberg previously reported that the two private equity groups were in talks over a deal to combine Southern and Mission. Rival company IVC Evidensia is owned by Sweden-based buyout group EQT, while PetVet is owned by KKR. Among the other biggest petcare clinic networks are AEA-backed AmeriVet Veterinary Partners and the veterinary health division of family-owned consumer group Mars, which operates more than 3,000 clinics worldwide. Southern, in which Shore has been an investor since 2014, operates more than 420 locations across the US, while Mission, which Shore helped to found in 2017, operates more than 330 vet hospitals nationwide.

> The single-minded pursuit of cost minimisation and profit maximisation leaves both customers and employees worse off.

Profit maximisation is the entire point of capitalist firms. I don't see the problem with this. I don't understand this nostalgia for small family businesses personally. If small businesses are better at running these local service businesses they'll be eventually prevail in the market anyway. I don't see the point of government interference in this matter.

> But with PE ownership expanding its roots across the economy and with institutional investors like pension funds and insurers contributing an increasing share of PE investments, there’s a greater case for regulation of PE firms on similar lines as public capital.

What is the matter with you? Anything and everything is a problem to be solved with government. After all government is true religion of India.