Thoughts on Affordable Housing VI

I have blogged about the challenge cities face in providing affordable housing, how vertical development is the only way to meet this challenge, how restrictive regulations stifle vertical development, and how this status quo is sustained by entrenched vested interests.

Urban planning is a good illustration of the vicissitudes of progress. For a long-time the only objective of urban planning was to ensure an ordered and planned development of the area. Zoning regulations were enacted to restrict cramped accommodation, prevent large shadows being cast thereby making cities dark, ensure sufficient utilities carrying capacity, and preserve or standardise the urban form.

Over time, these regulations, by restricting construction, led to the emergence of a price premium for properties in those areas. The existing landowners were naturally interested in preserving and maximising those premiums. They not only opposed measures that would increase supply and risk reduction of the premiums but also pushed for measures that erect more barriers to new construction. Many regulations like preservation of historic buildings and areas, green belts, higher parking requirements, more open spaces, and so on suited those already entrenched. Zoning came to be used as an instrument to preserve the status quo.

As the form and shape of these areas became frozen in a thicket of regulations, the expanding city started experiencing rising housing shortages and their prices so much so that it started to become a binding constraint on urban growth. The pressures to ease zoning restrictions and lower barriers to new construction began to rise. In fact, many global cities have reached a stage where further growth is possible only with renewal and easing of zoning regulations.

The Times has a set of excellent graphical articles on New York that illustrate the problems created by zoning regulations and how easing them can lead to the creation of more housing units.

Binyamin Applebaum tours the areas of New York where his ancestors lived and finds those properties are not only surviving but also could not have been built today. He describes the city as a “museum of family history” that preserves “the corporeal city of bricks and steel at the expense of its residents and of those who might live here”. He blames this on to interlocked regulatory barriers - zoning restrictions, tax code that penalises large apartment, rules that give neighbourhoods the power to veto redevelopment plans, and a byzantine permitting process. He writes that New York has witnessed sharp increase in housing rents in recent decades, climbing much faster than incomes.

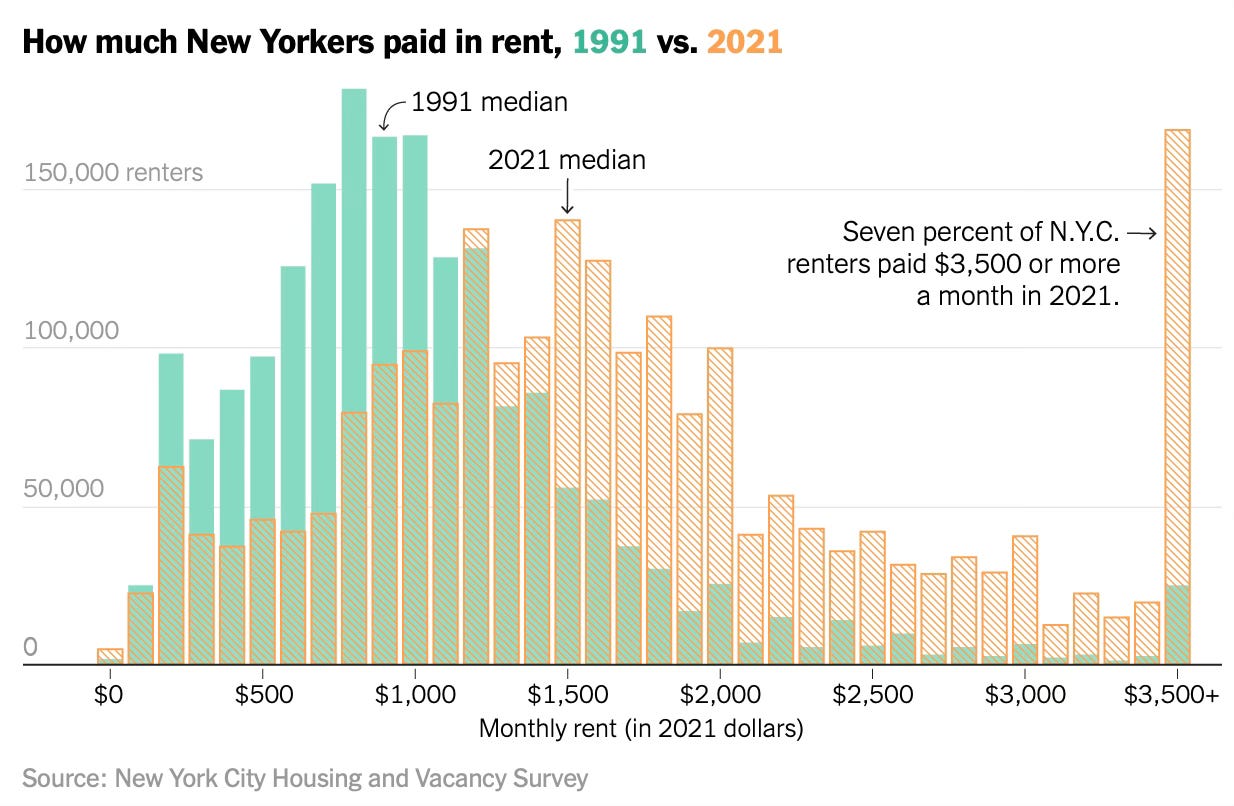

In 1991, the median rent in New York City was $900. By 2021, the median renter was paying $1,500 a month for housing.

Housing is taking up an increasing share of family incomes,

The average New Yorker now spends 34 percent of pre-tax income on rent, up from just 20 percent in 1965.

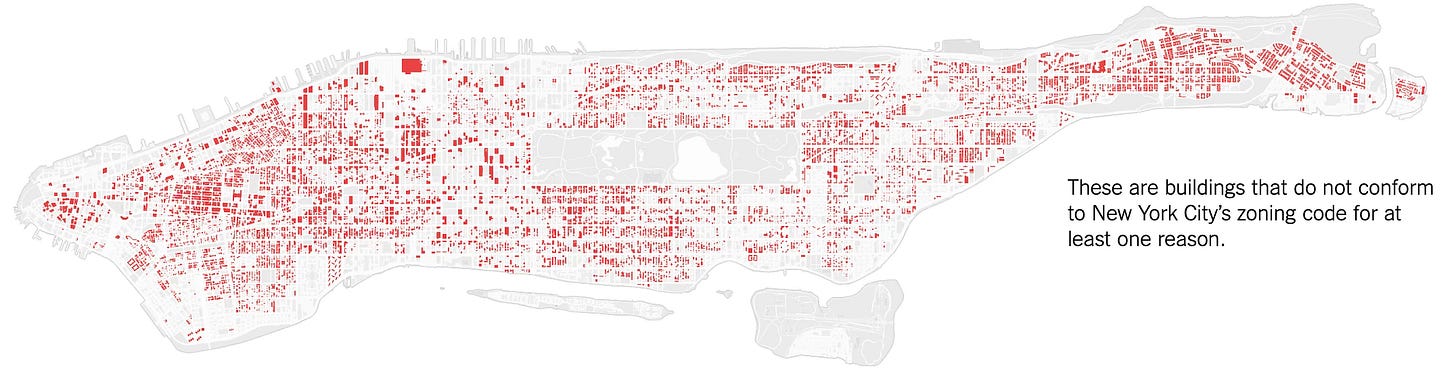

Another article has some great illustrations of how restrictive zoning regulations limit the construction possibilities in an area and how they have become progressively more restrictive since they were first approved in 1916. In fact 40% of restrictions in Manhattan could not have been built today. Roughly 15% of the land is reserved for single-family homes.

Whole swaths of the city defy current zoning rules. In Manhattan alone, roughly two out of every five buildings are taller, bulkier, bigger or more crowded than current zoning allows, according to data compiled by Stephen Smith and Sandip Trivedi. They run Quantierra, a real estate firm that uses data to look for investment opportunities. Mr. Smith and Mr. Trivedi evaluated public records on more than 43,000 buildings and discovered that about 17,000 of them, or 40 percent, do not conform to at least one part of the current zoning code. The reasons are varied. Some of the buildings have too much residential area, too much commercial space, too many dwelling units or too few parking spaces; some are simply too tall. These are buildings that could not be built today.

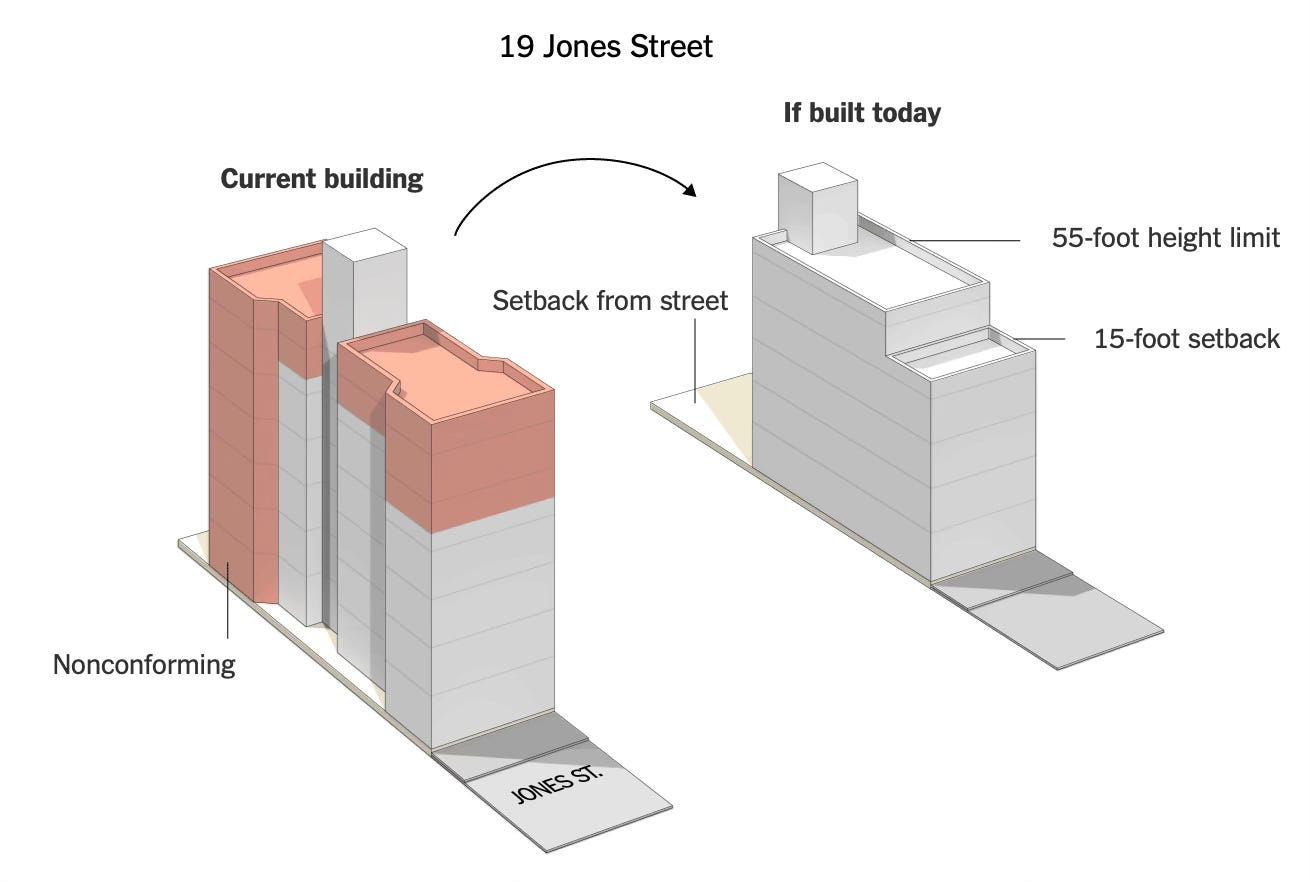

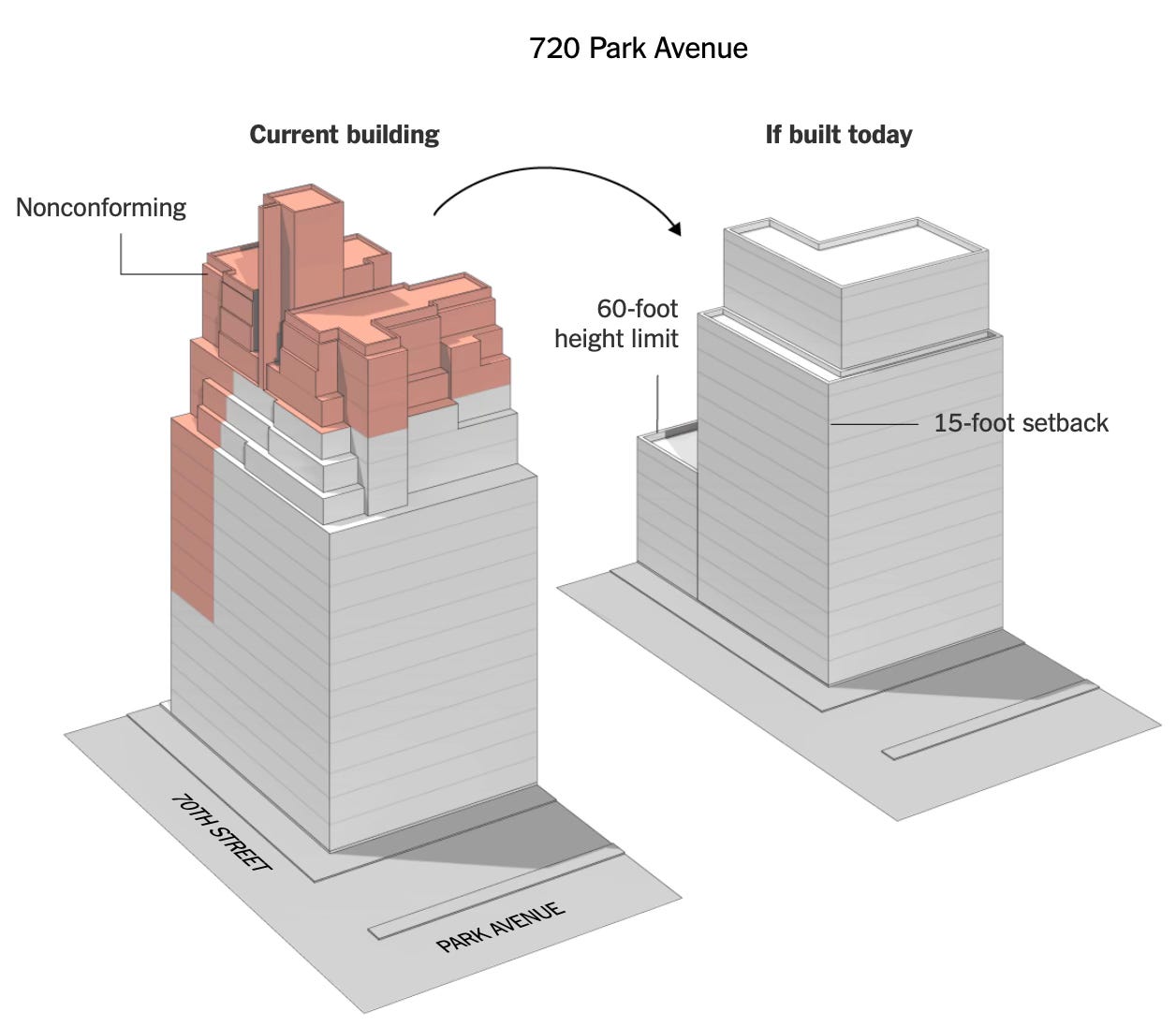

Here are two examples.

And this

Interestingly, nearly three-quarters of the existing square footage in Manhattan was built between the 1900s and 1930s.

The third article, an essay by Vishal Chakrabarthi a former Director of Planning for Manhattan, shows that 500,000 units to house 1.3 million people can be built in New York City by easing the zoning regulations but without radically changing the character of the city’s neighborhoods or altering its historic districts.

Apartments near public transit are convenient for residents and better for the environment, so we started by looking at areas within a half-mile of train stations and ferry terminals. Next, we excluded parts of the city that might be at risk of flooding in the future.In the remaining areas, we identified more than 1,700 acres of underutilized land: vacant lots, single-story retail buildings, parking lots and office buildings that could be converted to apartments. For each lot, we calculated how much housing we could add without building any higher than nearby structures… Last, we considered office buildings that could be converted to apartments… The hypothetical buildings in our analysis would add 520,245 homes for New Yorkers. With that many new housing units, more than a million New Yorkers would have a roof over their head that they could afford, near transit and away from flood zones, all while maintaining the look and feel of the city.

The fourth article describes the challenges of converting office complexes that have become vacant after the pandemic to residential units.

The deep interior of the modern office building, which is perfectly useful for windowless meetings and supply closets, is now largely useless for apartment living… The exterior window system on a building like this would need to be replaced at major expense, because these windows don’t actually open. These buildings have far more elevators than an apartment of the same size would want (adding either more expense in conversion or more wasted space). And in many downtown markets, a modern building like this is worth more per square foot in office rents than in apartment rents. As offices, these buildings can also rent 100 percent (or even more) of their total square footage, according to the quirky math of commercial real estate. That’s because some companies rent entire floors, but also because office tenants — unlike apartment renters — typically pay additional rent for shared building spaces beyond their suites.

To convert any of these properties to apartments, you’d have to add common corridors, bike storage, lounges, a gym — features that take up space but don’t collect rent (at least, not explicitly). In a typical residential building, only 80 to 85 percent of all square footage is considered rentable. That makes conversions particularly unappealing to many office owners… Then local rules add still more complexity: Maybe the building has to meet stricter seismic requirements as an apartment than as an office (much of the West Coast), or the whole facade must be replaced to meet current wind-load standards (hurricane-prone places). Or you can only convert 18 of the 32 existing office floors into residential use (in Manhattan, such use caps depend on a building’s age and location). Or units must average at least 500 square feet in size per building (downtown Chicago). Or every legal bedroom must have its own working window (New York requires this but Philadelphia and San Francisco don’t). Together, these constraints increase the cost of conversion and reduce the possible forms it can take.

This illustration of turning an existing office complex into a residential apartment shows the extent of challenges.

The large Indian cities are already at a stage where housing ownership within the city is unaffordable to all but the richest. Even the suburbs are fast being priced out of the reach of the emerging middle class. Those fortunate to have come in early and bought a property are wealthy rentier landlords enjoying the unearned increment from the city’s growth and housing scarcity. The only reason why things are not worse is because unlike ownership renting is still affordable.

Easing zoning regulations, and drastically at that, is becoming inevitable for these cities if they are to meaningfully address the housing supply problem.