Water privatisation unravelling in the UK

The UK is ground zero on the problems with the private equity-led infrastructure financing model. In early 2018, Carillion, the country's largest outsourcing provider, which provided different services to hundreds of public facilities in the UK, collapsed into compulsory liquidation. The entity had 19500 UK employees and 28500 pensioners had £5 billion in liabilities. The government was forced to step in and assume management of the schools, hospitals, and other public facilities being managed by Carillion.

Now comes news that Thames Water, the country's largest water utility, serving London and south-east of England and privatised in 1989, may be close to collapse and necessitate a public rescue. As interest rates have risen, the company's ability to service its £14 bn of debt is coming under strain. Besides a new rule mandates that from April 2025 regulated entities could not pay dividends if their credit rating falls below a certain threshold. The parent company, Kemble Water Holdings, 2026 bond plunged as much as 35 pence to 50 pence and distressed territory. The Chief Executive quit abruptly this week, leaving the government to consider the possibility of renationalisation.

The shareholders, consisting of a dispersed set of infrastructure, pension, and sovereign funds, have failed to make good on the £1.5 billion equity injection promised a year ago. Apart from skimping on investments, the utility, along with other UK water utilities, has come under the scanner for dumping sewerage into rivers and the sea. The FT's verdict on who's to blame is instructive,

Previous owners Macquarie, which helped grow Thames Water’s large debt pile, deserves blame.

The financial engineering that juiced up returns for investors has come at the cost of the utility's financial health,

Its net debt to ebitda ratio was 14 times at operating company Thames as of September 2022. For Kemble that figure was 22 times. Operating profits did not equal interest costs, with interest cover at 0.6 times and 0.3 times respectively. A high share of index-linked debt hurts, while indexed water rates lag behind interest payments. Whether Thames makes outsized returns is difficult to measure. Cash transferred from the operating company to investors via interest payments and dividends over the past decade comes to about £4.1bn, according to S&P data. Peers United Utilities and Severn Trent have paid out similar amounts. The difference at Thames is that three-quarters of that cash flow went as non-taxable interest payments to debtholders.

This summary of water privatisation in the UK makes disturbing reading,

After being sold with almost no debt at privatisation three decades ago, UK water companies have taken on borrowings of £60.6bn, diverting income from customer bills to pay interest payments. The entire sector is now under pressure from rising inflation, including soaring energy and chemical prices and higher interest payments on its debts. S&P, the rating agency, has negative outlooks for two-thirds of the UK water companies it rates — indicating the possibility of downgrades as the result of weaker financial resilience. More than half of the sector’s debt on average is inflation-linked. Ofwat said in December that it was concerned about the financial resilience of several water companies: Thames Water, Yorkshire Water, SES Water and Portsmouth Water. In 2021, Southern Water, which serves 4.2mn customers across Kent, Sussex and Hampshire, was rescued from the brink of bankruptcy after Australian infrastructure investor Macquarie agreed to take control of the company in a private deal with Ofwat.

In this context, FT has a long read which examines the role of Australian infrastructure fund, Macquarie in pioneering PE investments in infrastructure. The article points to two Macquarie UK infrastructure case studies (including Thames Water) that also highlights the problems with the model.

Macquarie first dipped its toe into the UK’s waters in 2003, with its shortlived acquisition of South East Water. After buying the company for £386mn from the French conglomerate Bouygues, Macquarie sold its final stake three years later for £665mn. During that period, debt — some of which was raised via a Cayman Islands subsidiary — increased more than fourfold from £87mn to £458mn. The increase in borrowing was used to pay investors more than £60mn in dividends as well as to pay off most of the costs of acquiring the company so that the final sales price was mostly profit... it was a loss for customers because a greater proportion of their bills — up from 8.7 per cent of turnover in 2002 to 14 per cent in 2006 — began to go towards paying the interest on debt.

... it and its co-investors acquired Thames Water, which now has 15mn customers in London and the Thames Valley, from German utility RWE for £4.8bn in 2006. One of the Macquarie consortium’s first acts was to arrange for Thames Water to pay a £656mn dividend in a year in which profits were just £241mn. Within six years, the group of companies managed by Macquarie had recovered all the money it and co-investors had spent on the acquisition, by borrowing against its assets and paying out dividends. By the time Macquarie sold its final stake in Thames Water in 2017, the company had spent £11bn from customer bills on infrastructure. But far from injecting any new capital in the business — one of the original justifications for privatisation — £2.7bn had been taken out in dividends and £2.2bn in loans. Meanwhile, the pension deficit grew from £18mn in 2006 to £380mn in 2017. Thames Water’s debt also increased steeply from £3.4bn in 2007 to £10.8bn at the point of sale, a sum still being paid off with interest by customers long after Macquarie has moved on.

The article sums up the problem of private finance in infrastructure

Now, more than three decades after privatisation first became popular, governments are faced with a conundrum: how they can use private finance in infrastructure in a way that delivers adequate returns for shareholders and deliver high quality services for the people — their voters — who are paying for them. “This is the issue of the decade,” says Folkman. “We know we want lots of investment to transition to net zero and even just to repair what’s failing. But if we want to make it work for investors as well as the public we need to figure out how to do it better and soon.”

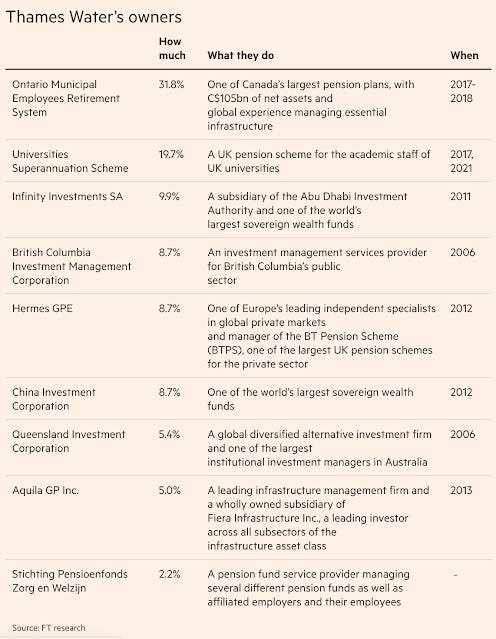

The first article points to Thames Water's ownership structure

And this graphic highlights the complicated holding structure.

Such complexity serves a purpose from the perspective of the private equity business model. But they distort incentives and set up the entity for failure.

Note the nature of the shareholders and their widely dispersed shareholdings, and the opacity of ownership and accountability added by the complex ownership holding structures. None of the investors have any water sector expertise. Nor do they have any interest in building an enduring and efficient water utility. All of them are playing the pass-the-parcel game. They are impersonal investors for whom Thames Water sits in their big portfolios as just another investment. Even the holding company, Kemble Water Holdings, is part of the pass-the-parcel game. There is nobody with the long-term stakes to take the life-cycle view and build an efficient water utility that serves its customers.

There is something to be said about ownership, and long-term at that, for such monopoly assets. It is essential for life-cycle management of such assets, especially those that are monopolies and deliver critical public services. Even if privatised, as the Europeans have done, the asset should be owned for the long-term by a physical company with expertise in the area and which can be held accountable by the government and customers. Regulators should take note of how the complexity of the holding company distorts incentives and comes in the way of life-cycle management of monopoly assets like utilities.

The problem with private equity in infrastructure should now be obvious. It's largely regulated and as an asset category is characterised by low but stable returns. Private equity firms seek to maximise returns. The returns profile of infrastructure assets does not allow for meeting the objectives of the PE firm and infrastructure funds.

In the circumstances, I am increasingly convinced that the likes of Macquarie are not the right kind of investors for regulated infrastructure assets (like roads and utilities). The returns expectations of their limited partners and the incentives of employees are so badly skewed. In the aggregate and over the long run, these structures end up doing more harm than good.

Start-ups with perceptive entrepreneurs and Boards try to be selective about the nature of their investors. They avoid certain kinds of investors who prioritise returns maximisation above all else. Such investor screening is even more important in essential public service sectors like infrastructure. Private equity and infrastructure funds are not the desirable kind of investors in the case of most infrastructure projects.